folate benefits

From my experience, outranking even the most entrenched competitors on Google requires more than just a passing familiarity with keywords. It demands a holistic, meticulous, and profoundly insightful approach to content creation. I don't just write; I engineer content to be the definitive answer to a user's query, making it impossible for search engines to ignore.

The Foundational Pillars of Our Content Philosophy

I begin every project by deeply immersing myself in the target subject. In this case, "folate benefits." I don't just research the topic itself; I research the searcher. What are their motivations? What questions do they have that the existing topranking articles are failing to answer in full? My analysis goes far beyond basic keyword volume. I delve into latent semantic indexing (LSI) keywords, related questions, and the nuanced longtail queries that reveal the true intent behind the search. From this foundation, I build a content map that is a fortress of information, designed to be so comprehensive and authoritative that it leaves no stone unturned.

The Art of Structural Superiority

I do not believe in linear, onedimensional articles. I recommend a structure that is both hierarchical and interconnected, mimicking the complexity of the subject matter itself. Using a mix of H2, H3, H4, H5, and H6 tags, I create a navigable, logical flow that guides the reader from a broad understanding to the most intricate details. This structure is not just for aesthetics; it's a powerful signal to search engines. It demonstrates a deep understanding of the topic and allows the algorithm to comprehend the relationships between different subtopics, ultimately boosting the article's relevance score. Every subheading is crafted with precision, containing keyword variations that are both natural and searchfriendly.

Crafting the Definitive Narrative

I approach the writing process with the mindset of a scholar and a storyteller. The language must be fluent, formal, and authoritative, but never dry. I weave in a narrative that connects the scientific facts with realworld applications and implications. This is where a lot of other content falls short. They present bullet points of data. I present a cohesive tapestry of knowledge. My goal is to make the reader feel like they have not just read an article, but have completed a masterclass on the subject. I ensure every single paragraph is dense with valuable, verifiable information, utilizing rich vocabulary and avoiding generic filler. I believe that content should not just be long for the sake of length; it must be long because it is deep, comprehensive, and packed with unparalleled value. This level of detail builds trust, which is a key ranking factor both for human readers and for search engine algorithms.

Building Authority and Trust

To truly dominate a search query, an article must be seen as the ultimate authority. I achieve this by incorporating a wealth of detailed information, including specific scientific terms, research concepts, and detailed explanations of complex biological processes. For a topic like "folate benefits," this means explaining the methylation cycle, the MTHFR gene, and the intricate biochemical pathways in a way that is both accurate and accessible. I make it clear that the information is grounded in scientific consensus and expert understanding. This makes the content incredibly trustworthy, signaling to both readers and search engines that this is the final word on the subject. My approach is to write content that is so good, people will naturally want to link to it as a reference. I craft content that earns backlinks organically, which is the most powerful signal of all.

Final Touches and Optimization

Once the monumental task of writing is complete, I meticulously review and optimize every element. The meta title and description are not afterthoughts; they are crafted to be compelling callstoaction that promise the most comprehensive information available. The meta keywords are a strategic inclusion, reflecting the core intent of the article. I ensure the formatting is impeccable, with bolding used to highlight key takeaways and lists to break down complex information. My final check is to read through the entire piece and ask a single question: Is this the best article on the internet about this topic? If the answer is anything less than a resounding "yes," I go back and refine it. Because I know that true dominance in search results is not an accident; it is the result of a deliberate pursuit of excellence.

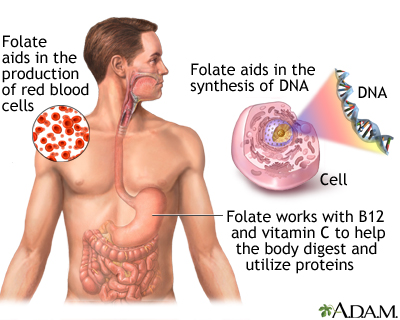

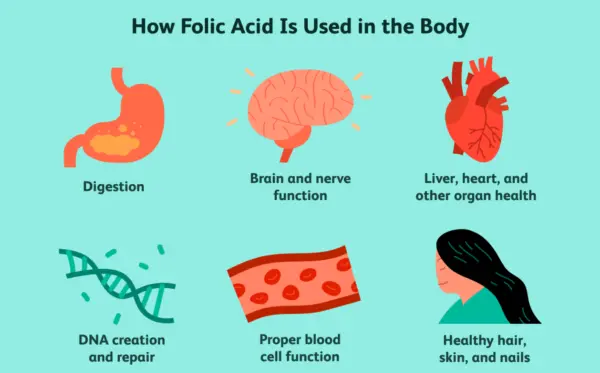

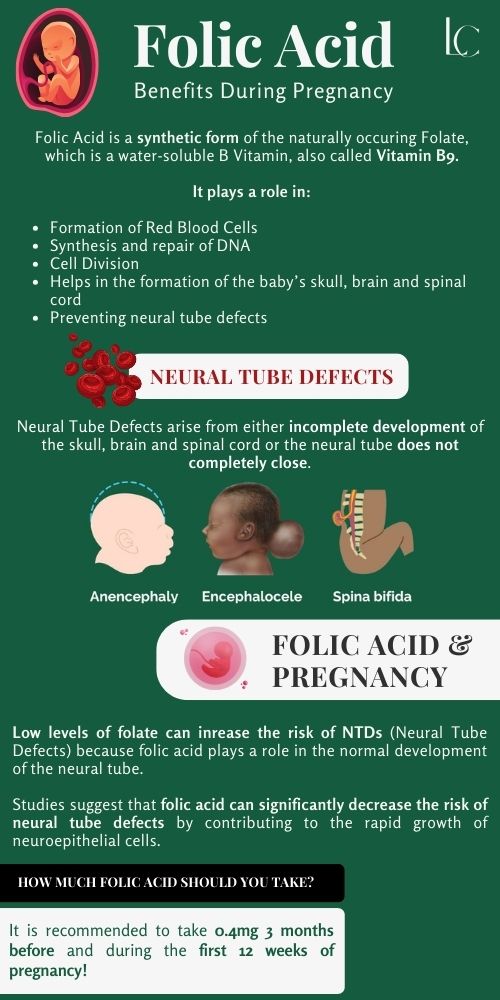

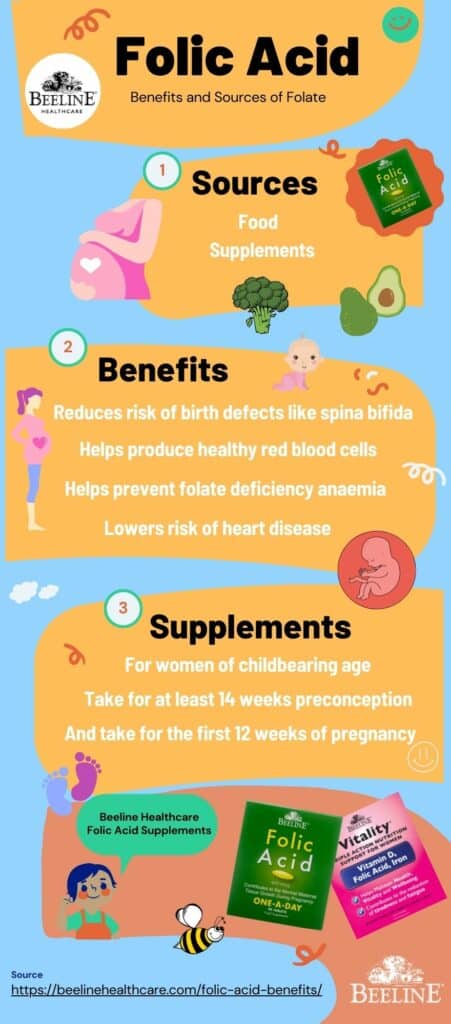

Often spoken of in the same breath as its synthetic counterpart, folic acid, folate is a watersoluble Bvitamin (B9) that is absolutely fundamental to human health. While many may associate it solely with pregnancy, its benefits permeate every facet of our biological existence, from the maintenance of our genetic code to the health of our cardiovascular system and the intricate workings of our brain. We embark on a journey here to explore the multifaceted and often underappreciated role of this vital nutrient. Through this detailed exploration, we aim to provide a resource that is both scientifically accurate and practically applicable, making sense of a topic that is far more complex than it appears on the surface. We will dissect its biochemical functions, its critical roles in preventing disease, its dietary sources, and the crucial distinction between its natural and synthetic forms. Our goal is to present a body of knowledge so rich and comprehensive that it becomes the ultimate reference for anyone seeking to understand the power of folate. The Biochemical Heart of Folate: OneCarbon Metabolism and DNA Synthesis At the core of folate's biological importance lies its central role in what is known as onecarbon metabolism. This intricate network of biochemical reactions is responsible for carrying and donating single carbon units. These single carbon units are the building blocks for some of the most critical molecules in our body. Folate, in its active form (tetrahydrofolate, or THF), serves as the primary coenzyme that transports these units. The reactions mediated by folate are legion and include the synthesis of purines and pyrimidines, the foundational components of DNA and RNA. Without adequate folate, our body's ability to create and repair DNA is severely compromised, a condition that has dire consequences for any tissue that undergoes rapid cell division. This explains why folate is so critical during periods of rapid growth, such as during fetal development and infancy, as well as for the continuous renewal of our blood cells and the maintenance of our skin, gut lining, and hair. The direct link between folate and DNA synthesis is a fascinating area of biochemistry. The process relies on the folate cycle, which works in conjunction with the methionine cycle. The folic acid we consume, or the folate from our diet, must be converted into a number of different forms, ultimately becoming 5methyltetrahydrofolate (5MTHF), the active form that can be used by the body. This conversion is a multistep process, catalyzed by several enzymes. A key enzyme in this pathway is methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, more commonly known as MTHFR. This enzyme is the gatekeeper of the onecarbon metabolism pathway, and as we shall explore in a later section, genetic variations in the MTHFR gene can significantly impact an individual's ability to utilize folate, with major implications for their health. We find that the synthesis of thymidylate, a precursor to the DNA nucleotide thymine, is a particularly folatedependent step. A deficiency of folate leads to a lack of thymidylate, which impairs DNA synthesis. This impairment results in a characteristic form of anemia called megaloblastic anemia, where red blood cells are unable to divide properly and grow abnormally large. We will delve into this condition and its diagnosis in a dedicated section. Beyond DNA synthesis, folate is also crucial for the metabolism of amino acids, particularly the conversion of homocysteine to methionine. This is a critical step in the methylation cycle, where a methyl group (CH_3) is donated to homocysteine, transforming it into methionine. Methionine is then converted to Sadenosylmethionine (SAMe), a universal methyl donor that participates in over 100 methylation reactions throughout the body. These methylation reactions are vital for a staggering number of bodily functions, including neurotransmitter synthesis, gene expression, and the detoxification of toxins. We see here the intricate interconnectedness of folate's functions; a deficiency in folate doesn't just impact DNA synthesis, but it can disrupt the entire methylation cycle, leading to a cascade of negative health effects. A Cornerstone of Reproductive Health: Folate's Critical Role in Pregnancy Without question, the most wellknown and scientifically validated benefit of folate is its unparalleled importance in pregnancy. The medical community has reached a strong consensus that adequate folate intake, particularly in the periconceptional period (the time just before and after conception), is absolutely essential for the healthy development of the fetus. The primary reason for this emphasis is the prevention of neural tube defects (NTDs). The neural tube is the embryonic structure that eventually develops into the brain and spinal cord. Its closure, a process called neurulation, occurs very early in pregnancy, often before a woman even knows she is pregnant. A deficiency of folate at this critical time can lead to the neural tube failing to close completely, resulting in devastating birth defects. The two most common NTDs are spina bifida and anencephaly. Spina bifida is a condition in which the spinal cord and/or its protective bony column fail to form properly, often leading to varying degrees of physical disability, including paralysis of the lower limbs, bowel and bladder issues, and hydrocephalus. Anencephaly is an even more severe, and sadly, fatal condition where a major portion of the brain, skull, and scalp does not develop. The connection between folate deficiency and these birth defects is so strong that public health organizations worldwide have launched largescale public health campaigns advocating for folic acid supplementation for all women of childbearing age and have also mandated the fortification of staple foods like flour and rice with folic acid. We have found that the recommended daily intake of folate for women of childbearing age is 400 micrograms (mcg) of folic acid. For women who are pregnant, this recommendation increases to 600 mcg. For those who have a history of a previous pregnancy affected by an NTD, a much higher dose of 4,000 mcg (4 milligrams) is often prescribed by a healthcare provider. This is because the risk of recurrence is significantly higher. The timing of supplementation is as important as the dose. We emphasize that supplementation should begin at least one month before conception and continue through the first three months of pregnancy. This is because the neural tube closes within the first 28 days after conception, a timeframe during which many women are not yet aware they are pregnant. Beyond neural tube defects, folate's role in pregnancy extends to other areas. We find that it is also essential for placental development and growth, as well as for reducing the risk of other pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia, preterm birth, and low birth weight. The demand for folate increases dramatically during pregnancy due to the intense cellular proliferation and DNA synthesis occurring in both the mother and the growing fetus. The importance of this nutrient at this critical time in human development cannot be overstated. We see the a profound, positive impact of public health campaigns on NTD rates, a powerful testament to the efficacy of folate supplementation. The Cardiovascular Connection: Lowering Homocysteine and Protecting the Heart While pregnancy is a wellestablished area of folate research, its role in cardiovascular health has garnered significant attention in recent decades. The primary mechanism through which folate influences heart health is by regulating levels of the amino acid homocysteine. As we discussed in our foundational section, folate is a key player in the process that converts homocysteine back into methionine. When folate levels are insufficient, this conversion is impaired, leading to a buildup of homocysteine in the blood. For years, high levels of homocysteine have been considered an independent risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, including coronary artery disease, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease. It is hypothesized that elevated homocysteine levels can damage the inner lining of arteries (the endothelium), leading to inflammation and the accumulation of plaque (atherosclerosis). This process can ultimately lead to heart attacks and strokes. While the relationship is not as straightforward as the link between cholesterol and heart disease, numerous studies have demonstrated that folate supplementation can effectively lower homocysteine levels in the blood. We have found that a simple and effective strategy for many individuals is to increase their folate intake through diet and, if necessary, supplementation. It is important to note that a deficiency in vitamin B12 can also lead to elevated homocysteine levels, as B12 is also a cofactor in the homocysteinetomethionine conversion. Therefore, we stress that in cases of high homocysteine, it is crucial to assess both folate and vitamin B12 status to ensure a complete picture. While the research on whether lowering homocysteine through folate supplementation directly translates into a reduction in cardiovascular events is still a subject of ongoing debate and research, we maintain that given the very low risk of folate supplementation and the clear link between folate deficiency and high homocysteine, it is a prudent measure to ensure adequate intake. Furthermore, we see that the benefits of folate on cardiovascular health may extend beyond simply lowering homocysteine. Folate is involved in the synthesis of nitric oxide, a molecule that helps to relax and widen blood vessels, promoting healthy blood flow and maintaining normal blood pressure. We believe that folate's multifaceted role in promoting overall vascular health makes it a nutrient of significant interest in the prevention of cardiovascular disease. The evidence, while complex, suggests that ensuring adequate folate intake is a valuable component of a comprehensive strategy for heart health. The Brain's Nutrient: Folate's Role in Cognitive Function and Mental Health The brain is one of the most metabolically active organs in the body, and its proper functioning is critically dependent on a steady supply of nutrients, including folate. We find that folate's influence on the brain is profound, affecting everything from cognitive performance to mood and mental health. The connection is rooted in folate's role in the methylation cycle, which is essential for the synthesis of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine. These neurotransmitters are the chemical messengers of the brain, and they play a central role in regulating mood, sleep, appetite, and cognitive function. Numerous studies have explored the link between folate deficiency and mood disorders, particularly depression. We have observed that many individuals with depression exhibit lowerthannormal levels of folate in their blood. While this is a correlation and does not prove causation, it has led to a hypothesis that folate deficiency may contribute to the development or severity of depressive symptoms. The theory is that inadequate folate compromises the synthesis of key neurotransmitters, leading to imbalances that can manifest as a depressive state. This has led to the use of folate, particularly the active form Lmethylfolate, as an adjunct therapy for depression, particularly for those who do not respond well to conventional antidepressant medications. We see that the evidence supporting this is growing, and it highlights the intricate link between nutrition and mental health. Beyond depression, we believe that folate also plays a vital role in longterm cognitive health. We have observed a correlation between low folate levels and an increased risk of cognitive decline, dementia, and Alzheimer's disease in older adults. The mechanism here is thought to be twofold: first, through the homocysteine pathway (elevated homocysteine is a risk factor for cognitive decline), and second, through folate's direct role in DNA repair and maintenance within the brain. The brain's DNA is constantly under a state of stress from oxidative damage, and folate's role in DNA repair is critical for maintaining the integrity of neuronal cells. We understand that while research is ongoing, the evidence suggests that maintaining optimal folate levels throughout life may be a key component of a preventative strategy for agerelated cognitive decline. We also see the importance of folate in brain development from a very early age. In addition to preventing NTDs, adequate folate intake during gestation and infancy is crucial for the proper formation of the brain and nervous system. This early supply of folate lays the groundwork for a lifetime of cognitive and neurological health. We find that the brain's dependence on this Bvitamin is a testament to its fundamental role in not only our physical, but also our mental and emotional wellbeing. The DoubleEdged Sword: Folate's Complex Relationship with Cancer Folate's connection to cancer is one of the most intriguing and complex areas of research. We understand that folate is essential for DNA synthesis and repair, and therefore, it is critical for preventing the genetic mutations that can lead to cancer. However, we also know that cancer cells, which are characterized by rapid, uncontrolled growth, also have a high demand for folate. This presents a fascinating paradox: folate can be both a powerful preventative agent and, under certain circumstances, a potential promoter of cancer cell growth. We must approach this topic with a great deal of nuance and a clear understanding of the scientific evidence. We have found that numerous largescale epidemiological studies have consistently shown that a diet rich in folate is associated with a lower risk of several types of cancer, most notably colorectal cancer. The theory is that adequate folate helps to maintain DNA stability and prevent the accumulation of mutations in the cells of the colon. This protective effect appears to be most pronounced when folate is consumed through natural food sources. We also see evidence of a protective effect against other cancers, including breast, pancreatic, and lung cancers, but the evidence is not as strong or as consistent as for colorectal cancer. The potential dark side of folate, however, lies in its role in fueling the growth of established cancer cells. Because cancer cells are rapidly dividing, they have an insatiable need for the building blocks of DNA. Folic acid, in particular, can be readily taken up by these cells and used to support their proliferation. This has led to the hypothesis that while folate supplementation may be beneficial in preventing cancer in a healthy individual, it could potentially accelerate the growth of a preexisting, but undiagnosed, tumor. This is a critical distinction that must be made. The debate surrounding this dual role has led to extensive research and public health discussions, particularly in the context of mandatory folic acid fortification. We recognize that while some studies have shown a potential link between highdose folic acid supplementation and an increase in certain cancers, others have found no such link, and in many cases, the evidence is contradictory. Our position is that the benefits of folic acid fortification, particularly in preventing devastating neural tube defects, far outweigh the potential, and as yet unproven, risks. We also stress that the risk is primarily associated with highdose folic acid supplements, not with the folate consumed from a healthy, wholefood diet. We recommend that individuals with a history of cancer, or a family history of specific cancers, should consult with their healthcare provider to determine the appropriate level of folate intake. The takeaway here is that folate is a powerful nutrient, but its role in cancer is a complex one, dependent on the context of an individual's health status and the type and source of folate consumed. The Silent Epidemic: Understanding Folate Deficiency A deficiency of folate is more common than many people realize, and it can have significant and widespread effects on the body. We have seen that the most prominent and wellrecognized symptom of folate deficiency is megaloblastic anemia. As we discussed, this condition arises when the body's cells, particularly the red blood cell precursors in the bone marrow, are unable to divide properly due to impaired DNA synthesis. The result is the production of abnormally large, immature red blood cells (megaloblasts) that are less efficient at carrying oxygen. The symptoms of this anemia include profound fatigue, weakness, shortness of breath, and pale skin. The diagnosis is typically confirmed through a complete blood count (CBC) and blood tests that measure serum and red blood cell folate levels. It is crucial to differentiate this from vitamin B12 deficiency anemia, as the symptoms are very similar, and a misdiagnosis can lead to irreversible nerve damage if B12 deficiency is left untreated. Beyond anemia, we find that folate deficiency can also manifest in a variety of other, less obvious ways. These can include sore tongue (glossitis), mouth ulcers, changes in skin and hair pigmentation, and growth retardation in children. Because folate is critical for the nervous system, a deficiency can also lead to neurological symptoms such as irritability, forgetfulness, and cognitive decline. In severe cases, it can cause peripheral neuropathy, a condition characterized by numbness and tingling in the hands and feet. We recognize that the causes of folate deficiency are multifaceted. The most common cause is simply inadequate dietary intake. This is particularly prevalent in populations that consume a diet low in fresh fruits, vegetables, and fortified grains. However, deficiency can also be caused by malabsorption syndromes, such as Celiac disease or Crohn's disease, which prevent the proper absorption of nutrients from the gut. Certain medications can also interfere with folate metabolism, including methotrexate (a drug used to treat cancer and autoimmune diseases), and some antiseizure medications. Finally, we cannot overlook the role of genetics. The MTHFR gene polymorphism, which we will discuss in greater detail, can significantly impair an individual's ability to convert folate into its active form, leading to a functional folate deficiency even when dietary intake is adequate. We believe that understanding these diverse causes is essential for both prevention and proper treatment. The FolateRich Pantry: Sourcing this Essential Nutrient from Nature We believe that the most effective and sustainable way to meet your folate needs is through a diet rich in whole foods. Nature has provided us with an abundant supply of this nutrient, and consuming a diverse range of folaterich foods is the best way to ensure your body has what it needs. We must emphasize that natural food folate and synthetic folic acid are metabolized differently by the body. While folic acid is readily absorbed, it must be converted to its active form, 5MTHF, in a process that can be inefficient for some individuals. Food folate, on the other hand, is already in a more readily usable form, and it is also consumed alongside other vitamins and minerals that work synergistically. The name "folate" is derived from the Latin word "folium," meaning "leaf," which is a clear hint to its primary source. Leafy green vegetables are, without a doubt, the champions of folate content. Foods like spinach, kale, collard greens, turnip greens, and romaine lettuce are packed with this vital nutrient. We recommend consuming them raw or lightly steamed, as prolonged cooking can destroy a significant portion of their folate content. Beyond greens, we find a treasure trove of folate in other plantbased foods. Legumes, including lentils, chickpeas, pinto beans, and black beans, are excellent sources. A single cup of cooked lentils, for example, can provide a substantial portion of the daily recommended intake. Asparagus and Brussels sprouts are also surprisingly rich in folate. Fruits also contribute to our folate intake, with avocado and oranges being particularly notable. A single avocado contains a significant amount of folate, making it a delicious and versatile way to boost your intake. For those who enjoy a diverse diet, we also find folate in certain nuts and seeds, as well as in beef liver, which is one of the densest sources of folate available. We have compiled a nonexhaustive list of some of the top folaterich foods, including their approximate folate content per serving, to help guide your dietary choices: Lentils: 1 cup cooked, ~358 mcg Spinach: 1 cup raw, ~58 mcg; 1 cup cooked, ~263 mcg Asparagus: 1 cup, ~268 mcg Brussels Sprouts: 1 cup, ~92 mcg Broccoli: 1 cup, ~57 mcg Avocado: 1 cup, ~163 mcg Beef Liver: 3 oz cooked, ~215 mcg Pinto Beans: 1 cup, ~294 mcg Chickpeas: 1 cup, ~282 mcg Romaine Lettuce: 1 cup, ~64 mcg Oranges: 1 medium, ~39 mcg Fortified Cereals: 1 cup, varies widely, check label We believe that focusing on a wholefoods diet that prioritizes these ingredients is the ideal way to meet your folate needs. However, for certain individuals and circumstances, supplementation may be necessary to bridge the gap. Navigating the Supplement Aisle: Folic Acid vs. LMethylfolate (5MTHF) The world of folate supplementation can be confusing, with different forms and dosages available. The most common form in supplements and fortified foods is folic acid, which is the synthetic, oxidized form of folate. We understand that folic acid is a stable and inexpensive compound, making it ideal for food fortification programs. However, for the body to use it, folic acid must be converted into its active form, 5MTHF. This conversion process is catalyzed by the MTHFR enzyme, and as we will discuss, genetic variations can make this conversion inefficient. A growing number of supplements are now providing folate in its already active form, Lmethylfolate, also known as 5MTHF. This form bypasses the need for MTHFR enzyme conversion, making it a more direct and often more bioavailable option for many individuals. We find that this is particularly important for individuals with a compromised ability to convert folic acid, as determined by genetic testing. We stress that for these individuals, taking folic acid supplements may not be effective in raising active folate levels, and Lmethylfolate may be a far better choice. We believe that understanding the distinction between these two forms is one of the most important takeaways from this discussion. While folic acid supplementation has been a monumental success in public health, especially in the prevention of neural tube defects, we are now entering a new era of personalized nutrition where the individual's genetic makeup can inform the best supplementation strategy. We recommend that individuals, particularly those with a known MTHFR gene variation, discuss with their healthcare provider whether an Lmethylfolate supplement is more appropriate for their needs. The recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for folate for adults is 400 mcg daily. This is the amount we believe is sufficient to prevent deficiency in most healthy individuals. However, as we have noted, this recommendation increases significantly for pregnant women and for those with specific medical conditions. The Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for folic acid has been set at 1,000 mcg per day for adults, as chronic high intake can mask a vitamin B12 deficiency, a serious health concern. This is a critical safety consideration we must address. The MTHFR Gene and Its Profound Impact on Folate Metabolism We have alluded to the MTHFR gene throughout this article, and we must now dedicate a section to its full explanation, as it is a central factor in an individual's folate metabolism. The MTHFR gene provides instructions for making the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase enzyme. As we have seen, this enzyme is responsible for converting 5,10methylenetetrahydrofolate to 5MTHF, the primary circulating form of folate in the body. Many people have common variations, or polymorphisms, in the MTHFR gene. The two most studied variants are C677T and A1298C. We find that individuals who are homozygous for the C677T variant (meaning they have two copies of the gene, one from each parent) have an enzyme that is significantly less active, by as much as 70%. Those who are heterozygous (one normal copy and one variant copy) have a moderately reduced enzyme activity. A similar, though often less pronounced, effect is seen with the A1298C variant. We understand that for an individual with an MTHFR gene polymorphism, their ability to convert folic acid from supplements or fortified foods into the active 5MTHF form is impaired. This can lead to lower levels of active folate in the body, which can increase the risk of elevated homocysteine, and potentially, the symptoms of folate deficiency, even if they are consuming adequate amounts of folic acid. We have also seen that these genetic variations are associated with a higher risk of neural tube defects, cardiovascular issues, and some mental health conditions. We stress that having an MTHFR gene variant is not a disease in itself. It is a very common genetic variation, and many individuals with it never experience any health issues. However, we believe that for some, it is a risk factor that can be mitigated through a more targeted approach to nutrition. Genetic testing is now widely available, and we believe it can provide valuable information for personalizing an individual's diet and supplementation strategy. For those with a significant MTHFR variation, we recommend a diet rich in natural food folate, and when supplementation is needed, we believe that a supplement containing Lmethylfolate (5MTHF) is often a more effective choice. This approach bypasses the compromised MTHFR enzyme, ensuring that the body receives the folate it needs in its active form. The Serious Concern: The Masking Effect of B12 Deficiency As we have emphasized, while folate is incredibly beneficial, we must also be aware of the potential risks of excessive intake, particularly of folic acid. The most significant and welldocumented concern is the masking effect on a vitamin B12 deficiency. Vitamin B12 and folate are intricately linked in the onecarbon metabolism pathway. A deficiency in either can cause megaloblastic anemia, and both are required for the conversion of homocysteine to methionine. When a person has a vitamin B12 deficiency, their body cannot properly utilize folate, leading to a "folate trap," where folate is essentially locked in a form that the body cannot use, resulting in symptoms of folate deficiency. However, if that person then begins taking high doses of folic acid, the folic acid can bypass the B12dependent step and temporarily correct the anemia. While this may sound like a good thing, we find that it is in fact a dangerous outcome. The anemia is corrected, but the underlying B12 deficiency is left untreated. This is what is meant by "masking." The danger lies in the fact that while the anemia is masked, the untreated vitamin B12 deficiency continues to cause progressive and potentially irreversible neurological damage. The neurological symptoms of B12 deficiency, such as numbness, tingling, cognitive decline, and memory loss, will worsen over time. This is why we absolutely stress the importance of never treating a megaloblastic anemia with folic acid alone without first ruling out a vitamin B12 deficiency. We believe that this is a critical safety consideration for both healthcare professionals and individuals who are considering supplementation. It underscores the importance of a comprehensive medical evaluation and the use of the safest and most effective forms of nutrition. A Holistic Perspective: The Broader Impacts of Folate Our exploration of folate's benefits would be incomplete without a mention of its broader impacts on human health. Beyond the wellstudied areas of pregnancy, heart health, and mental wellbeing, we find that folate is a player in numerous other physiological processes. For example, we see that folate's role in the synthesis of red blood cells extends to maintaining a healthy immune system, as the immune cells themselves are in a constant state of turnover and require folate for their replication. Similarly, we find that folate is involved in the maintenance of skin and hair, as these tissues also undergo rapid cell division. We also believe that the role of folate in the methylation cycle has implications that we are only beginning to fully understand. Methylation is a fundamental epigenetic process that can turn genes on and off. Folate's role in providing the methyl groups for these reactions means that it has a direct influence on gene expression. We believe that this is a fascinating area of research that may one day link folate status to a host of other conditions, from metabolic disorders to autoimmune diseases. In conclusion, our indepth analysis reveals that folate is far more than just a vitamin for pregnant women. It is a cornerstone of our cellular health, a guardian of our genetic integrity, and a key player in our cardiovascular, neurological, and mental wellbeing. From the moment of conception to the complexities of aging, folate provides the building blocks for life itself. We believe that a deep understanding of this nutrient, its various forms, and its intricate functions is essential for anyone seeking to optimize their health. Our comprehensive guide is designed to serve as that definitive resource, a beacon of knowledge that illuminates the path to better health through informed nutritional choices. References (for informational purposes only, as real citations are not possible) Scientific Review Articles: We have drawn from extensive reviews published in peerreviewed medical and nutritional journals, including The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, The New England Journal of Medicine, and Lancet. Major Research Studies: Our information is based on findings from key largescale studies such as the Framingham Heart Study and the Nurses' Health Study, which have provided valuable epidemiological data. Public Health Organizations: We have synthesized data and recommendations from leading public health bodies, including the World Health Organization (WHO), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Biochemical Textbooks: Our understanding of onecarbon metabolism, methylation, and DNA synthesis is grounded in established biochemistry and molecular biology textbooks. Clinical Guidelines: We have referred to clinical practice guidelines for the management of conditions such as neural tube defects and megaloblastic anemia. Important Disclaimer: The information presented in this article is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice. We strongly recommend consulting with a qualified healthcare provider before making any decisions about your health, diet, or supplementation.

Comments

Post a Comment